In the early decades of modern medicine, radiation was seen not as a danger—but as a miracle. The ability to see inside the human body without a single incision was hailed as one of science’s greatest triumphs. X-ray machines, introduced in the late 19th century, transformed diagnostics and changed medicine forever.

But behind the glowing screens and gleaming hospital equipment, a quieter truth unfolded: progress had outpaced understanding. What was once called “healthy energy” would later be recognized as one of the most dangerous exposures in medical history.

The Age of Radiant Optimism

By the 1920s and 1930s, X-rays had become a symbol of modernity. Hospitals, private clinics, and even department stores proudly displayed X-ray machines as proof of technological sophistication. Many believed radiation was harmless.

One of the most striking examples was the shoe-fitting fluoroscope, a device found in American and European shoe stores. Children would slip their feet into a box while parents and clerks admired the glowing outline of tiny bones. The machines emitted strong doses of radiation—often hundreds of times higher than what is now considered safe.

At the same time, radium—a naturally radioactive element discovered by Marie and Pierre Curie—was celebrated as a wonder substance. It glowed beautifully in the dark, and marketers quickly found ways to sell it. Health tonics, toothpaste, cosmetics, and even drinking water were infused with trace amounts of radium and promoted as sources of “vitality” and “energy.”

The Tragic Case of Radithor

One of the most infamous products of this era was Radithor, a drink containing water and radium salts, sold in the United States in the 1920s and early 1930s. It was marketed as an “energy elixir,” with endorsements from athletes and socialites.

Industrialist Eben Byers, a well-known Radithor consumer, reportedly drank large quantities daily. After several years, he developed severe radiation poisoning, losing most of his jawbone before his death in 1932. His case became a turning point in public awareness of radiation’s dangers. When his remains were later examined, they were still radioactive—an eerie reminder of how misunderstood the substance once was.

The tragedy led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to strengthen oversight of radioactive products, effectively banning “radiation tonics” and unregulated radium-based consumer goods.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120314084032Thomas-Edison-Fluoroscope-1896-470.jpg)

The Medical Embrace of X-rays

Despite these warnings, X-rays continued to be used enthusiastically through the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Physicians used radiation to treat acne, remove unwanted hair, and shrink enlarged tonsils or thymus glands in children.

A well-known example was the use of radiation therapy for acne, common in the 1940s and 1950s. While it produced temporary improvements, decades later, many of those treated developed thyroid disorders or cancers linked to radiation exposure.

At the time, this wasn’t negligence—it was limited knowledge. Scientists and physicians genuinely believed that the doses were safe. The long-term effects of low-level radiation exposure simply weren’t yet understood, and protective standards did not exist.

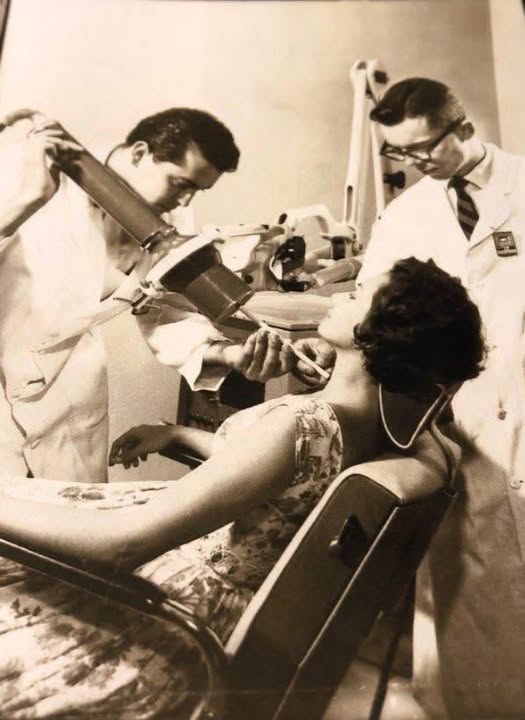

Historical photographs from the era—patients under massive X-ray machines, doctors standing close without lead aprons—show how trust in technology overshadowed caution.

When Knowledge Caught Up

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, evidence had become impossible to ignore. Researchers began linking repeated medical radiation exposure to higher rates of certain cancers, particularly thyroid cancer and leukemia among medical staff.

The scientific community responded decisively. Regulatory agencies such as the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) and national health authorities introduced strict exposure limits and mandatory safety protocols.

-

Lead aprons and thyroid shields became standard equipment for patients and technicians.

-

Radiologists began operating machines from behind protective barriers.

-

Routine X-rays for children or dental visits became less frequent, moving from “annual” to “only when necessary.”

-

Radiation doses were reduced dramatically thanks to technological advances and improved imaging sensors.

These measures saved lives—and transformed how modern medicine balances innovation with safety.

The Hidden Cost of Overconfidence

For those who lived through the early radiation era, many of these safeguards arrived too late. Workers who painted luminous watch dials with radium, known as the Radium Girls, developed severe radiation sickness, bone loss, and cancers. Their courage in speaking out led to landmark occupational safety reforms.

Patients treated with excessive radiation for minor ailments often faced serious health consequences years later. Many of the physicians themselves, exposed daily in the line of duty, developed illnesses now recognized as radiation-related.

The lesson was clear: technological progress must always be guided by long-term evidence and ethical caution.

What the Photograph Teaches Us

A photograph taken in 1963—a woman reclined in a medical chair, doctors hovering nearby, no protective equipment in sight—captures that moment in history perfectly. It is both a testament to optimism and a symbol of misplaced trust.

Those physicians weren’t villains. They were professionals working with the best information available at the time. The patient likely believed she was receiving the most advanced care possible. Both were participants in a system that equated novelty with safety.

From today’s perspective, the image feels unsettling. We now understand that radiation exposure, especially to the thyroid gland, carries significant risks. But in that sterile, fluorescent-lit room, no one knew.

From Radiation to Reflection

The journey from the unshielded X-ray machines of the past to the precision imaging of today is one of medicine’s most profound evolutions. Modern radiology is now built on safety: digital imaging uses lower doses, technicians receive continuous monitoring, and patients are informed of potential risks and benefits before exposure.

Still, the photograph from 1963 remains a powerful reminder that progress without humility can be dangerous.

Every era has its blind spots. In the early 20th century, it was radiation. Today, it might be something else—an untested chemical, a new therapy, or a digital health trend whose long-term impact remains unknown. The challenge is to learn from history: to question, to test, and to proceed carefully even when innovation seems irresistible.

The Legacy of Learning

Medicine’s story is not one of failure, but of growth. Every mistake—painful as it was—led to greater understanding. The victims of early radiation exposure shaped safety protocols that protect millions today.

They turned tragedy into progress.

Modern radiology, nuclear medicine, and cancer therapy now operate within carefully calculated safety limits that would have been unimaginable in the 1960s. We can thank those early decades for showing the necessity of responsible science, data transparency, and patient protection.

Conclusion: The Light That Warns

The history of radiation in medicine teaches one enduring truth: technology without accountability can harm the very people it aims to heal.

What once seemed like “healthy energy” turned out to be invisible danger. Yet from that misunderstanding emerged the safety standards that define medical practice today.

That 1963 photograph still matters—not as a story of guilt, but as a story of awakening. It reminds us that every discovery carries both promise and risk, and that the pursuit of healing must always be guided by evidence, humility, and care.

Because progress is not just about moving forward.

It’s about remembering what we once didn’t know—and making sure we never forget it again.